By: Mike Smith , Ellen Findlay , David Hawker

*Available directly from our distributors, click the Available On tab below

David Hawker was born in Surrey and educated at Kingston Grammar School. He studied Medicine in Edinburgh, where he met his wife, Beryl, who is also a doctor. He then specialised in Anaesthetics before working in both mission and government hospitals in Pokhara, Nepal for nine years, bringing up their three children there. Returning to the UK, he worked as a GP in Cornwall for 18 years, then on the Hebridean islands of Islay and Jura. He played, and then umpired cricket for 60 years, and loves travel and trains. He has 11 grandchildren. His first book Kanchi Doctor was the biography of one of Nepal’s first surgeons.

David Hawker was born in Surrey and educated at Kingston Grammar School. He studied Medicine in Edinburgh, where he met his wife, Beryl, who is also a doctor. He then specialised in Anaesthetics before working in both mission and government hospitals in Pokhara, Nepal for nine years, bringing up their three children there. Returning to the UK, he worked as a GP in Cornwall for 18 years, then on the Hebridean islands of Islay and Jura. He played, and then umpired cricket for 60 years, and loves travel and trains. He has 11 grandchildren. His first book Kanchi Doctor was the biography of one of Nepal’s first surgeons.

David Hawker was born in Surrey and educated at Kingston Grammar School. He studied Medicine in Edinburgh, where he met his wife, Beryl, who is also a doctor. He then specialised in Anaesthetics before working in both mission and government hospitals in Pokhara, Nepal for nine years, bringing up their three children there. Returning to the UK, he worked as a GP in Cornwall for 18 years, then on the Hebridean islands of Islay and Jura. He played, and then umpired cricket for 60 years, and loves travel and trains. He has 11 grandchildren. His first book Kanchi Doctor was the biography of one of Nepal’s first surgeons.

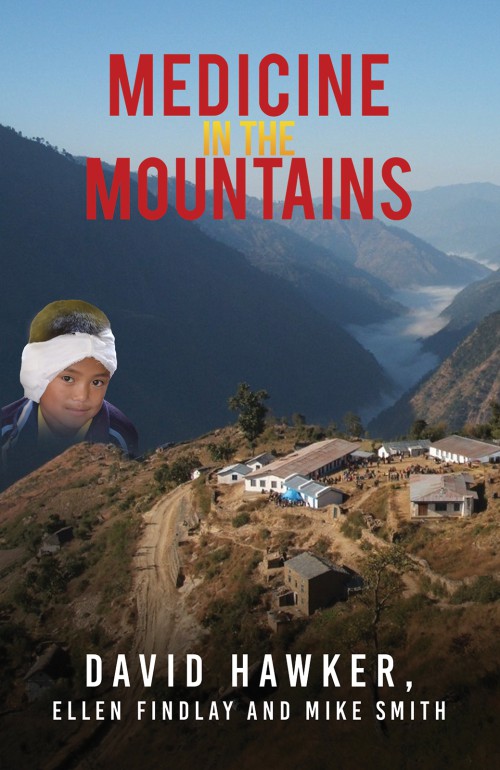

Occasionally, among all the complaining and dissatisfaction so prevalent in our culture today, a truly good news story comes along. This is one of them. Heartwarming and inspirational, it tells of one woman's vision, and sheer doggedness, in gathering specialist medical teams - surgeons, anaesthetists, nurses - willing to go (at their own expense) to bring transformative medical care to isolated mountain communities in Nepal. Achieving mind-boggling numbers of operations and consultations in a crammed week or so at a time, they coped with hair-raising travel, challenging treks, and primitive conditions and makeshift facilities, far removed from homeside comfort and shiny western hospital theatres. It changed their lives as well as those of the 100,000 or more men, women and children they treated, plus in the process developing long-term medical, surgical and dental skills in the Nepali doctors and nurses who joined one camp or another. As a result, Nepal now has specialist centres to carry on this work, staffed by nationals. Read, be thankful, and be inspired as to how small seeds of faith can produce such an enduring harvest.

The heroic endeavour to extend medical care into the remote mountain villages of Nepal is vividly captured in the challenging stories in this book. Providing volunteer medical temporary “camps” – often concentrating on prevalent ear problems – meant lugging quantities of supplies, often by foot, into settlements high up in the hills and far beyond anything we might consider to be a road! Years of faithful and undaunted care made the project popular with the poorest people of the land. They often walked days to get treated, and then ask “Why have you people bothered to come here and help us?”.

Over the years both government and revolutionary forces came to respect the project, and the resultant expansion of Nepali state medical services is a testament to the vision of those who inspired and embodied such care. I would have welcomed more detail about these developments, even if it meant an abbreviation of some of the stories.

To better picture a little of what was involved, I enjoyed using a software flight simulator to visit isolated airstrips near some of the villages mentioned! Other online maps and photos of the terrain also provided further intriguing information.

I have just finished reading “Medicine in the Mountains”. It’s an heroic story of commitment and faith among incredibly needy communities and the recognition from Nepalis of love that they found extraordinary.

Mike Smith and Ellen Findlay’s contributions to health needs in the Himalayas over so many years are outstanding. There are many vivid things to note - the beauty of the landscapes, the poverty of the people, the harshness of their living conditions that varied from area to area, the conditions that volunteers had to endure, danger on the roads and threats from civil unrest, vehicle breakdowns, scary flights, recurring funding issues, the creativity of so many to find practical solutions in ‘operating theatres’ that are far from any sterile norm, and the raising up of local leaders to take over the baton.

You should be proud of putting all this on record. Absolutely fascinating and humbling.

MANY congratulations for `Medicine in the Mountains!` It brings to life a section of INF`s work that I always felt was most impressive. It all happened after I left my work in Nepal, but Ellen Findlay`s letters kept me in touch. You have skilfully woven the narrative around her letters, other volunteers` letters, Mike Smith`s input, and many other contributions. I was amazed at the dedication of the teams, their expert care amid difficult travel and fairly filthy living conditions!

A beautifully presented book, the quality of the paper used is unusual, a pleasure to turn each page. Here is biography, a book dedicated to the full adult lives of Christian medical missionaries Ellen Finlay and to a lesser extent Mike Smith. The backdrop is that colourful exciting landlocked country Nepal.

Nepal where the two major religions Hinduism, and Buddhism sit side by side in harmony. Nepalese people utilising guidance from their many gods, often in an calm acceptance of Karma, peaceful acceptance of life’s good and the bad. Like most missionaries however the book emphasised that “The Christian God” is the driving force of missionary healing zeal. For these individuals this guidance led to their charity work. They were focused, believed their lives working in remote impoverished areas of this 3rd world country was inspired and guided by their unique one god the Trinity God that is Christianity.

History of Nepal is interesting and fully explained in this book, especially the interplay of government and charity initiatives through 40 or so years. Accounts of funding for medical initiatives, the organisation, logistics of access to remote areas is fascinating. Most of the book is set in the recent historic time when Nepal was in its civil war with The Maoists. Especially highlighted is what Ellen Finlay saw as her struggle to overcome Maoist interference that could destroy her rural clinics. A view that sets an exciting edge to this narrative. However this interference to her work never actually happened to her, and I wonder if there was exaggeration in letters back to Britain and elsewhere acted as a catalyst prompting much generous “out of country” funding: Or is it just her over anxiousness organising these very ambitious but ultimately successful medical projects?

Yes civil unrest was happening, at the time, roadside army posts manned by armed soldiers, were on routes to and from the capital Kathmandu, general strikes, bunds, a name for public demonstrations, were fairly regular. But usually, in my experience at the time, 1998 to 1992 these all occurred without particular violence, albeit in Kathmandu and Pokhara. All the usual commercial popular Himalayan trekking routes were open and being used at that time, without noticeable Maoists interference.

This book, as a history of medical initiatives in rural Nepal after the country opened its borders to the outside world; as a medical textbook of how to accomplish extreme operations and medical emergencies in the most bizarre and difficult of circumstances, is very informative; as a insight to inaccessible areas of impoverished Nepal, very good.

Helping to bring medicine to remote Himalayan villages

Forty-five years ago this autumn, my wife Jan and I joined six others to help drive a Land Rover 8,500 miles overland from Plymouth to deliver it to a leprosy hospital in Pokhara, Nepal.

The aim of the project was to help the International Nepal Fellowship treat leprosy and TB sufferers in the remote villages of this Himalayan country.

But when I read David Hawker’s book, Medicine in the Mountains, I was delighted to read that our Land Rover had been used in many other ways, including taking staff and equipment to set up surgical and dental camps in isolated communities.

Inspiring account of recent pioneering medical work in Nepal

This is a truly inspiring account of the fulfilling of the vision of a remarkable Scottish nurse, Ellen Findlay, and an English ENT Surgeon, Mike Smith, to provide specialist medical and surgical care through camps in the mountains of Nepal. The author, Dr David Hawker, himself worked in Nepal for a number of years and later helped out at one of the camps, so he writes with real empathy and insight.

Working with the International Nepal Fellowship in Pokhara, western Nepal, Ellen and Mike became aware that the rural population in the mountains had no access to modern medical and surgical care due to poverty, poor infrastructure and distance. The Government was only beginning to attempt to build clinics and small hospitals, but these were poorly staffed. After prayer and some surveys, in the early 1990s they decided to hold a week-long ENT camp in a mountainous area. This was such a success, with 400 patients and 17 operations, that they began to hold them regularly in different areas.

Using volunteer specialists from Britain and elsewhere they carried out 130 camps in various specialities over the next 25 years, despite difficult travelling conditions, political upheaval, the Maoist insurrection, and unreliable vehicles, including helicopters. This work was supported by donations and was a real venture of faith. Having worked as a surgeon in rural India, I am full of admiration for the teams of Nepalis and expatriates who arranged and carried out these camps in primitive conditions, dealing with advanced disease.

Opportunity was taken to train junior Nepali surgeons and eventually INF were able to build two specialist hospitals in Pokhara and Surkhet, in cooperation with the Government, one for ENT and one for gynaecology. It is to be hoped that the Nepali Government can continue to develop the infrastructure and improve preventive and primary health care alongside education in the rural areas.

I thoroughly recommend this book.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and for marketing purposes.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies